David Grun, founder of Israel.

David Grun, a.k.a. David Ben-Gurion used extreme violence and mass murder to satisfy his religious belief that Palestine belongs to Jews and to establish the State of Israel on Palestinian land.

DailyBeastie.Com

7/29/202540 min read

David Grun used extreme violence and mass murder to satisfy his religious belief that Palestine belongs to Jews and that Palestinians were troublemaking squatters to be exterminated and expelled from their homes to form a Jewish state on Palestinian land.

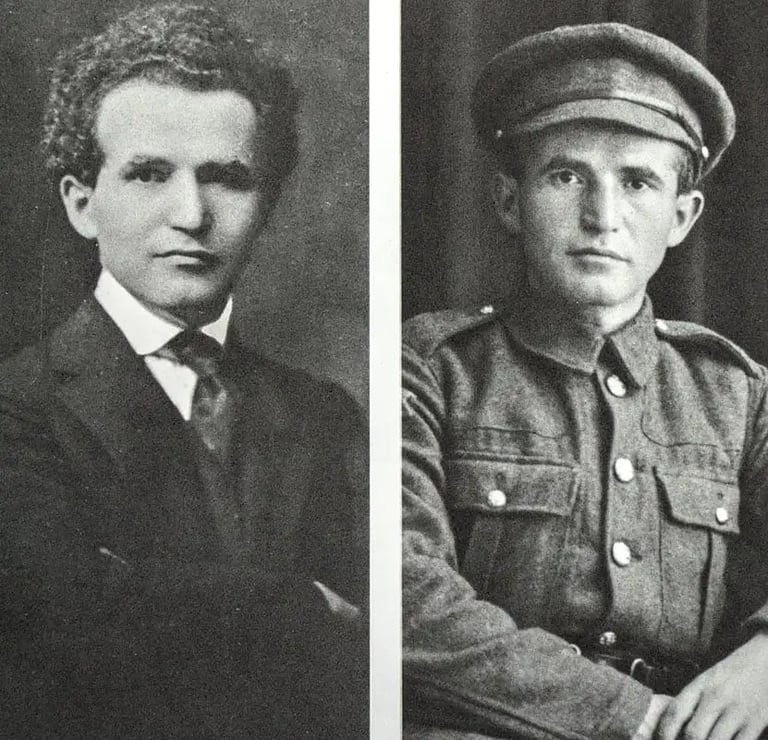

David Grun, a.k.a. David Ben-Gurion was born on October 16, 1886 in the Soviet Union, Plonsk, Poland to Polish Jewish parents.

David Grun, four foot, eleven inches tall was known as DAVID BEN GURION, MEMBER OF THE 40TH ROYAL FUSILERS IN WORLD WAR I.דוד בן גוריון במדי הגדוד המלכותי ה-40 של מלחמת העולם הראשונה.

The Jewish Legion was a series of battalions of Jewish soldiers who served in the British Army during the First World War.

Some participated in the British conquest of Palestine from the Ottomans.

The formation of the battalions had several motives: the expulsion of the Ottomans, the gaining of military experience, and the hope that their contribution would favorably influence the support for a Jewish national home in the land when a new world order was established after the war.

The idea for the battalions was proposed by Pinhas Rutenberg, Dov Ber Borochov and Ze'ev Jabotinsky and carried out by Jabotinsky and Joseph Trumpeldor, who aspired for the battalions to become the independent military force of the Yishuv in Palestine.

Their vision did not fully materialize, as the battalions were disbanded shortly after the war.

However, their activities significantly contributed to the establishment of paramilitaries such as the Haganah and the Irgun (which later became the foundation for the Israel Defense Forces).

The Zion Mule Corps was a volunteer body formed in March 1915 in Alexandria from mainly Russian Jewish emigres (who could not be directly enlisted in the British Army).

It played an imporant role in getting supplies up to the front lines at Gallipoli, but was disbanded in May 1916.

Veterans of the Mule Corps served in the 20th Londons until the formation of the 38th "Judean" Battalion, Royal Fusiliers in August 1917.

In 1918 the 39th RF was raised in Nova Scotia from American and Canadian Jews, and the 40th in Palestine from mainly Ottoman Jews.

The 41st and 42nd Battalions were Depot Battalions based in Plymouth.

The three Service Battalions took part in the fighting in the Jordan Valley and the Battle of Megiddo in 1918, becoming known as the Jewish Legion.

Although the soldiers of all five battalions were demobilised soon after November 1918, many of them remained in Palestine to pursue their Zionist hopes, and the First Judaeans continued as a unit with its own distinctive Menorah capbadge.

His father, Avigdor Grün, was a pokątny doradca (secret adviser), navigating his clients through the often corrupt Imperial legal system.

Following the publication of Theodore Herzl's Der Judenstaat in 1896 Avigdor co-founded a Zionist group called Beni Zion—Children of Zion.

In 1900 it had a membership of 200.

At the age of 14 he and two friends formed a youth club, Ezra, promoting Hebrew studies and emigration to the Holy Land.

In 1904 Ben-Gurion moved to Warsaw where he became involved in Zionist politics and in October 1905 he joined the clandestine Social-Democratic Jewish Workers' Party—Poalei Zion.

Two months later he was the delegate from Płońsk at a local conference.

While in Warsaw the Russian Revolution of 1905 broke out and he was in the city during the clampdown that followed; he was arrested twice, the second time he was held for two weeks and only released with the help of his father.

In December 1905 he returned to Płońsk as a full-time Poalei Zion operative.

There he worked to oppose the anti-Zionist Bund who were trying to establish a base.

He also organized a strike over working conditions amongst garment workers.

He was known to use intimidatory tactics, such as extorting money from wealthy Jews at gunpoint to raise funds for Jewish workers.

Ben-Gurion discussed his hometown in his memoirs, saying:

“For many of us, anti-Semitic feeling had little to do with our dedication [to Zionism].

I personally never suffered anti-Semitic persecution.

Płońsk was remarkably free of it ... Nevertheless, and I think this very significant, it was Płońsk that sent the highest proportion of Jews to Eretz Israel from any town in Poland of comparable size.

We emigrated not for negative reasons of escape but for the positive purpose of rebuilding a homeland ... Life in Płońsk was peaceful enough.

There were three main communities: Russians, Jews and Poles.

The number of Jews and Poles in the city were roughly equal, about five thousand each.

The Jews, however, formed a compact, centralized group occupying the innermost districts whilst the Poles were more scattered, living in outlying areas and shading off into the peasantry.

Consequently, when a gang of Jewish boys met a Polish gang the latter would almost inevitably represent a single suburb and thus be poorer in fighting potential than the Jews who even if their numbers were initially fewer could quickly call on reinforcements from the entire quarter.

Far from being afraid of them, they were rather afraid of us. In general, however, relations were amicable, though distant.”

In autumn of 1906 he left Poland to go to Palestine.

He travelled with his sweetheart, Rachel Nelkin, and her mother, as well as Shlomo Zemach, his comrade from Ezra. His voyage was funded by his father.

12 Things You Need to Know About David Ben-Gurion

1. David Grun was born in Plonsk, Poland (then part of the Russian Empire) in October 1886. His father was a lawyer and ardent Zionist. In this case, the apple didn’t fall far from the tree. The son was educated in a Hebrew school and at age 14, with two friends, formed Ezra, a club intended to promote emigration to Palestine. Its members spoke only Hebrew among themselves.

2. As a student at the University of Warsaw, he joined Poalei Zion. In the 1905 uprising that shook the Tsarist regime, he was arrested. In 1906 he left for Palestine, though he insisted that it was not because life in Poland had become untenable; rather it was “for the positive purpose of rebuilding a homeland….Life in Plonsk was peaceful enough.” Following his arrival in Jaffa, he was elected to the central committee of the newly formed branch of Poalei Zion.

3. At age 20 he was involved in creating the first agricultural workers’ commune (“Kvutzah,” eventually “Kibbutz”). He was a laborer, picking oranges in Petach Tikvah, doing other agricultural work in the Galilee, withdrawing from politics. In 1908 he joined an armed group acting as watchmen at Sejera and fought a skirmish there. Then he volunteered with Hashomer, a force of volunteers being organized to guard isolated settlements.

4. In 1911 he went to Thessalonika to learn Turkish in preparation for law school. By 1912, he was studying law in Istanbul. It was then that he adopted the name David Ben-Gurion (after the medieval historian Joseph Ben Gurion).

5. At the start of World War I, he was living in Jerusalem. Believing that the future of the Jews lay with the Ottoman Empire, he joined with Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (with whom he’d attended school in Istanbul, and who would later become Israel’s second president) to recruit a Jewish militia to assist the Turks.

No dice: he and Ben-Tzvi were deported anyway, in March of 1915.

They made their way to the United States, where they tried to raise funds for an army to fight for Turkey.

He married in New York in 1917; and that same year following the issuing of the Balfour Declaration, he changed his thinking about what was best for the Jews.

In 1918 he returned to Palestine as a member of the Jewish Legion to fight with the British against the Ottomans.

6. Following the war, and through the 1920s, Ben-Gurion increasingly took leadership of labor politics.

Amid opposing ideas and factions, he was a founder of Histradut, which became a central force in the economic and social affairs of the Jews under the British Mandate.

Its role, as he saw it, was to build a Jewish economy under the leadership of a Jewish working class.

Labor Zionism became dominant in the World Zionist Organization, and by 1935 he was chairman of the Zionist Executive, the movement’s highest directing body, and head of the Jewish Agency, its executive branch.

As such, he led the struggle for an independent Jewish state.

He was an early supporter of the partition of Palestine, having tried in the 1920s to make peace with the Arabs, and failed.

Initially a proponent of restraint with regard to using violence, he called for a “fighting Zionism” when Britain took a pro-Arab stance on the even of World War II.

7. He believed the Negev offered an opportunity for Jews to settle unimpeded and settled in a kibbutz there called Sde Boker.

He also resided in Tel Aviv in what is now called Ben-Gurion House.

It was in Tel Aviv in May 1948 that he declared the new State of Israel, a nation that, he said, would “uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race.”

Had he ever doubted this time would come? In 1946, he’d met and become friends in Paris with Ho Chih Minh. The latter offered a Jewish home-in-exile in Vietnam.

Ben-Gurion turned it down, certain that a government would be established in Palestine. So it’s fitting that he was the first to sign the Israeli Declaration of Independence, which he’d helped write, and that he became the first Prime Minister.

8. He knew war would immediately come, and when it did he looked upon it as a means to conquer – and therefore confirm ownership of – the land.

To do so, he consolidated the army, uniting the various Jewish militias – by force, when necessary – into the IDF, the Israel Defense Force.

9. As the first Prime Minister, he built state institutions and oversaw development of the country, including the absorption of great numbers of diaspora Jews.

Among the national projects he presided over: “Operation Magic Carpet,” the airlift of Jews from Arab countries; construction of new towns and cities, settlements in the Negev, and construction of the national water carrier; creation of a unified school system.

One controversy (there were many, but this one stood out) surrounded his working with West Germany to secure compensation for Nazi Germany’s treatment of Jews. Reparations in the amount of $715 million were paid.

10. Ben-Gurion continued in office as Prime Minister and then Minister of Defense and then Prime Minister again, until 1963, when he stepped down from office.

In 1970, he retired from political life entirely. His years in office were marked by remarkable events (Suez Canal campaign, capture of Eichmann, establishment of a secret nuclear facility, to name a few), and always by intense political conflict.

Even today, historians argue about his actions toward the Arabs, whether or not he was involved in a policy of forced expulsion.

11. What cannot be denied is the extraordinary way in which he combined a vision of Jewish unity with pragmatic politics and military tactics – plus a great sense of humor. Charismatic and controversial, he remains one of history’s great characters.

Time Magazine named him one of the hundred most important people of the twentieth century.

Consider this summary just a start: a dozen things can’t begin to scratch the surface of Ben-Gurion’s life and contributions.

He wrote memoirs and published his collected speeches and essays.

“Anyone who believes you can’t change history has never tried to write his memoirs.”

“If an expert says it can’t be done, get another expert.”

12. David Ben-Gurion died of cerebral hemorrhage in December 1973. He is buried alongside his wife, Paula, at Midreshet Ben-Gurion, a research center in the Negev.

“No. Actually he opposed communism since the beginning of his political career.

Economically speaking he was a social democrat.

Much like some west European leaders at the time like Clement Attlee.

A supervised economy, with lots of nationalization of infrastructure, but with lots of place for private initiative.

Giving free education and health services, but enabling free trade and capitalistic venture.

When Israel was founded in 1948 he based it upon democratic principles including free elections.

No 'dictatorship of the proletariat' Bolshevic style.

It is true that his Mapay party was a very strong ruling party, somewhat reminicent of communist parties in eastern Europe at the time.

But this resemblance is superficial.

There were no violent measures against the opposition.

Elections were frequent and free.

He himself gave up political power of his own will a few times.

Something a Bolshevic would never do.

The Israeli Communist Party was marginalized in his time.

He is famous for saying that any government he would head would not include Herut or Maki.

Herut is Begin's party.

Now known as Likud, and is the ruling party in the last decades.

Maki are the communists.

A Bolshevic would not leave Maki out of his government.

In the international arena he would oppose Stalin and the USSR.

He was strongly allied with France.

And kept close to the US.

Even though in his coalitions were parties who wanted to drive Israel closer to the eastern bloc, he was pro western from the beginning, giving a solid base to the strong alliance with the US which is the basis of Israeli foreign policy to this day.

A Bolshevic would choose the other side in the cold war.

A true social democrat, and the founder of Israeli democracy, Ben Gurion is anything but a Bolshevic.”

Israeli Communists (the Maki Party) brandishing pictures of Stalin and Lenin in the Labor Day parade in Tel Aviv, May 1 1949.

Was David Ben Gurion a Bolshevik?

Gal Amir, PhD in Law, University of Haifa

David Ben-Gurion opposed the Israeli Communist party known as the “Maki Party” who metamorphisized into the Likud Party.

Herut Party

חֵרוּת

Leaders

Menachem Begin (1948–1951)

Aryeh Ben-Eliezer (acting 1951-1952)

Menachem Begin (1952-1983)

Yitzhak Shamir (1983–1988)

Founded 15 June 1948 - Dissolved 1988 - Merged into Likud Headquarters Tel Aviv, Israel Newspaper Herut Ideology - National conservatism and Revisionist Zionism

Political position Right-wing to far-right National affiliation

Gahal (1965–1973)

Likud (1973–1988)

Most MKs 28 (1981, 1984) Election symbol

Herut MKs Uri Zvi Greenberg, Esther Raziel Naor, and Menachem Begin, at the first meeting of the Knesset in Jerusalem

Herut (Hebrew: חֵרוּת, lit. 'Freedom') was the major conservative nationalist political party in Israel from 1948 until its formal merger into Likud in 1988. It was an adherent of Revisionist Zionism.

Early years

Foundation and platform

Herut was founded by Menachem Begin on 15 June 1948 as a successor to the Revisionist Irgun, a militant group in Mandate Palestine.

The new party was a challenge to the Hatzohar party established by Ze'ev Jabotinsky.

Herut also established an eponymous newspaper, with many of its founding journalists defecting from Hatzohar's HaMashkif.

Objection to withdrawal of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and negotiations with Arab states formed the party's main platform in the first Knesset election.

The party vigorously opposed the ceasefire agreements with the Arab states until the annexation of Gaza Strip and the West Bank, both before and after the election.

Herut differentiated itself by refusing to recognise the legitimacy of the Kingdom of Jordan after the armistice, and frequently used the slogan "Two banks of the Jordan River" in claiming Israel's right to the whole of Eretz Israel/Palestine because of their historical significance in religious Jewish texts.

According to Joseph Heller, Herut was a one-issue party intent on expanding Israel's borders.

Herut's socio-economic platform represented a clear shift to the right, with support for private initiative, but also for legislation preventing the trusts from exploiting workers.

Begin was at first careful not to appear anti-socialist, stressing his opposition to monopolies and trusts, and also demanding that "all public utility works and basic industries must be nationalized."

Herut was from the outset inclined to sympathise with the underdog, and, according to Hannah Torok Yablonka, "tended to serve as a lodestone for society's misfits.”

1949 elections

Herut's political expectations were high as the first election approached in 1949.

It took credit for driving the British government out and as a young movement, reflecting the esprit of the nation, it perceived its image as being more attractive than the old establishment.

They hoped to win 25 seats, which would place them second and make them leader of the opposition, with potential for a future gain of government power.

This analysis was shared by other parties.

At the elections, Herut only won 14 seats with 11.5 percent of the votes, making it the fourth-largest party in the Knesset; Hatzohar, on the other hand, failed to cross the electoral threshold of 1 percent and disbanded shortly thereafter.

Opposition to Herut

Though practical differences between the two parties were less dramatic than the rhetoric suggested, both the Labor Zionist establishment and the opposition Herut emphasised those differences to mobilise their voters.

The hostility between Begin and Israel's first Prime Minister, the Mapai leader David Ben-Gurion, which had begun over the Altalena Affair, was evident in the Knesset.

Ben-Gurion coined the phrase "without Herut and Maki" (Maki was the Communist Party of Israel), a reference to his position that he would include any party in his coalition, except those two.

In fact, Herut was approached at least three times (1952, 1955, and 1961) by Mapai for government negotiations; Begin turned down each offer, suspecting that they were designed to divide his party.

The ostracism also expressed itself in the Prime Minister's refusal to refer to Begin by name from the Knesset Podium, using instead the phrase "the person who sits next to M. K. Badar", and boycotting his Knesset speeches.

Ben-Gurion's policy of ostracising Revisionism was performed systematically, as seen in the legal exclusion of fallen Irgun and Lehi fighters from public commemoration and from benefits to their families.

Herut members were excluded from the highest bureaucratic and military positions.

An open letter to The New York Times. The letter was signed by over twenty prominent Jewish intellectuals, including Albert Einstein, Hannah Arendt, Zellig Harris, and Sidney Hook.

Herut also met fierce resistance from the broader Jewish diaspora.

When Begin visited New York City in December 1948 over twenty prominent Jewish intellectuals, including Albert Einstein, Hannah Arendt, Zellig Harris, and Sidney Hook signed an open letter to The New York Times.

The letter condemned Herut and Begin for their part in the Deir Yassin massacre and likened the party "in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties" and accused it of preaching "an admixture of ultranationalism, religious mysticism, and racial superiority."

Decline

In the municipal elections of 1950, Herut lost voters to the centrist General Zionists, who also attracted disillusioned voters from Mapai and established themselves as a tough opposition rival to Herut.

At the second national convention, Begin was challenged by more radical elements of his party.

They wanted a more dynamic leadership, and thought he had adapted himself to the system.

At the convention, Begin's proposal to send children abroad for security reasons, although there was a precedent for such a measure, sounded defeatist, and it was unanimously rejected.

It was considered to have hurt the party's image.

In March 1951, Herut lost two of its Knesset seats, with the defection of Ari Jabotinsky and Hillel Kook from the party to sit as independent MKs.

Referring to previous written commitments, the party sought to revoke its Knesset membership, but the issue was still not settled by the next election three months later.

Critics of the party leadership pointed out that the party had changed and lost its status as a radical avant-garde party.

Uncompromising candidates had been removed from the party list for the upcoming elections, economic questions loomed large in the propaganda, and Mapai had co-opted some of the Herut agenda, not least by declaring Jerusalem as Israel's capital.

These critics and outside commentators thought that Herut seemed irrelevant.

In the 1951 elections, Herut won eight seats, six less than previously.

Begin resigned as leader, a move he had considered before the election because of the internal criticism.

He was replaced by Aryeh Ben-Eliezer, whose leadership was nipped in the bud when he suffered a heart attack in late 1951.

Ya'akov Rubin became party secretary general.

Despite sending the party his resignation letter in August 1952 and going abroad to Europe, the party's national council voted instead to make Ben-Eliezer deputy chairman and grant Begin a six month leave of absence.

Begin did not return to public life until January 1952, prompted to do so by the growing debate around the Reparations Agreement between Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany.

As a young party without institutions paralleling those of Mapai, who were predominant in most areas of social life, Herut was at a serious disadvantage.

Its leaders were politically inexperienced and clung to the principle of not – as representatives of the entire nation – accepting financial support from any interest groups.

They were prevented from building a strong and competent party structure because of this.

Begin's return

Menachem Begin addressing a mass demonstration against negotiations with Germany in Tel Aviv 1952.

Party membership card in 1956. Note similar logo as the Irgun Gang

The Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany of 1952 brought Begin back into politics.

It gave the party new momentum, and it proved an effective weapon against the General Zionists.

The Reparations Agreement awoke strong sentiments in the nation, and Begin encouraged civil disobedience during the debate on the affair.

The largest demonstrations gathered 15,000 people, and Herut reached far beyond its own constituency.

The party let the issue fade from the agenda only after having wrested a maximum of political capital from it.

The third national convention included a fierce debate about democracy and legitimate political actions.

There was strong sentiment in favour of using the barricades, but Begin vigorously resisted it.

The government of the nation, he claimed, could only be established via the ballot box.

The convention gave Begin important legitimacy by sending a message to the public that the party was law-abiding and democratic.

At the same time, it secured the support of the hard-liners who would not compromise on its principles.

Economic and fiscal policy were given greater emphasis, and the party attacked the Histadrut for its dual role as employer and trade union.

It proposed to outlaw such concentration of power and also abolish party control of agricultural settlements.

Herut reasoned that workers were empowered by private enterprise.

A 25 per cent tax cut was also envisioned.

In the 1955 election, the party nearly doubled its seats to 15, and became the second-largest party in the Knesset, behind Mapai.

Apart from an improved campaign, the accomplishment was attributed to the activist party platform in a situation of deteriorating security, to more support from recent immigrants and other disgruntled elements, and to disillusionment with the economic situation.

The Kastner trial also played into Herut's hands, when, together with Maki, they helped bring down Moshe Sharett's government in 1954 through a motion of no-confidence over the government's position in the trial.

Herut added another seat in the 1959 elections, feeding on feelings of resentment against the dominant left that existed mainly among new Sephardi and Mizrahi immigrants.

The party failed, however, to maintain the momentum of the previous election, and to make substantial gains, as had been hoped.

As the young nation grew stronger, the public did not feel the same existential dread, lessening the impact of Herut's activist message, especially after the Suez crisis, in which Ben-Gurion's performance was perceived favourably.

The Wadi Salib riots a few months before the election caused the government to play the role of maintainer of law and order, which resonated well among the middle class.

Mapai exploited the situation successfully by depicting Begin as dangerous.

Gahal alliance

Herut helped bring down the government again in 1961 when they and the General Zionists tabled a motion of no confidence over the government's investigation into the earlier Lavon Affair; in the resulting 1961 election, the party maintained its 17 seats.

Toward the end of the Fifth Knesset in 1965, and in preparation for the upcoming election, Herut joined with the Liberal Party (itself a recent merger of the General Zionists and the Progressive Party) to form Gahal (a Hebrew acronym for the Herut-Liberal Bloc (Hebrew: גוש חרות-ליברלים, Gush Herut-Liberalim)), although each party remained independent within the alliance.

The merger helped moderate Herut's political isolation and created a right-wing opposition bloc with a broader base and more realistic chance to lead the government.

The full alliance did not survive, however, because seven members of the Liberal Party, mostly former Progressives, soon defected from the Liberals and formed the Independent Liberals; they disagreed with the merger, identifying Herut and Begin as too right-wing.

Mapai also experienced defections at the time, and the Knesset session closed with Gahal holding 27 seats, second only to Mapai's remaining 34.

Under Ben-Gurion, public commemoration of fallen Irgun and Lehi militants was strictly refused.

Under Levi Eskhol, however, they began to be rehabilitated, indicating a more equal status for Revisionism and Herut.

Over time, the public perception of both Herut and its leader had changed, despite the ostracism imposed by Prime Minister Ben-Gurion.

Begin had remained the main opposition figure, against the dominant politicians of the left, particularly in debates regarding such heated issues as the Lavon investigation and Israel's relationships to Germany.

This prominence evaded much of the ostracism's impact, and Ben-Gurion's hostility became ever more savage.

He eventually started to liken Begin to Hitler – an attitude that backfired, making Begin to stand out as a victim.

The political climate took a favourable turn for Revisionism and Herut in mid-1963, when Levi Eshkol replaced Ben-Gurion as Prime and Defense Minister.

A government resolution in March 1964 calling for the reinterment of Zeev Jabotinsky's remains in Israel attests to this.

Fallen Irgun and Lehi militants also began to be commemorated more equally, with their reputations being rehabilitated.

In the 1965 elections, Gahal won only 26 seats, well below that of the left's new Alignment, which won 45.

In Herut's search for a scapegoat, its leadership was questioned by many; they considered that Begin, despite his achievements, brought an indelible stigma from his militant days before and around independence, scaring off voters. Internal opposition arose, and Herut's eighth convention in June 1966 became turbulent.

The opposition group sensed that Begin's leadership position was too strong to challenge; so, they concentrated on winning control over the party organization.

They won overwhelming victories in all votes for the composition of party institutions.

Begin responded by putting his own political future at stake.

He threatened to leave the party chair, and maybe also his seat in the Knesset.

Begin's move mobilized delegates in emphatic support for him, but the party convention still ended with great internal tension, and without a party chairman; the chair would be vacant for eight months.

Party opposition to Begin' leadership came to a showdown a month after the convention, when Haim Amsterdam, an assistant to one of the opposition leaders, Shmuel Tamir, published a devastating attack on Begin in Ha'aretz; this led to the suspension of Tamir's party membership.

The leaders of the opposition then established a new party in the Knesset, the Free Center, with the loss of three seats for Herut.

After this revolt, Begin returned to party leadership.

Government participation

This article is part of a series on Conservatism in Israel

Agudat Yisrael

Degel HaTorah

Likud

National Religious Party–Religious Zionism

New Hope

New Right

Noam

Otzma Yehudit

Shas

Yisrael Beiteinu

Defunct

Ahi

Eretz Yisrael Shelanu

Hatikva

Hatzohar

Herut

The Jewish Home

Kach

Moledet

National Religious Party

Religious Zionist Party

Tehiya

Yisrael BaAliyah

Gahal joined the government on the first day of the Six-Day War, with both Begin and the Liberal's Yosef Sapir becoming a Minister without Portfolio; Ben-Gurion's Rafi also joined, with Moshe Dayan becoming Defense Minister.

The national unity government was Begin's own brainchild.

This had a significant positive effect on his image.

Critics agree that it was a major turning point in Herut's road to power, since it granted it the legitimacy it had been denied up until then.

The national unity government was more than an emergency solution in a time of existential danger; it reflected a relaxation of ideological tension, which enabled the government to outlive the emergency.

Moreover, Begin and Ben-Gurion were reconciled.

Ben-Gurion needed him in his bitter rivalry with Eshkol and Begin surprised his adversary by proposing to Eshkol that he should step aside in favor of Ben-Gurion as the leader of an emergency government.

The proposition was turned down, but Ben-Gurion, who recently had compared Begin to Hitler, now praised his responsibility and patriotism.

The outcome of the war strengthened Herut.

The principle of the indivisibility of the land had seemed like an archaic principle with little practical significance, but now, it emerged from the fringe of consciousness to the core of national thought.

Begin saw it as his first mission in the government to secure the fruits of the victory by preventing territorial withdrawal and promoting settlement.

Despite the breakaway of the Free Center, Gahal retained its representation in the Knesset in the 1969 elections, and several of their candidates were elected as mayors.

Herut was included in the new government of Golda Meir with six ministers (out of 24).

The recruitment of Major-General Ezer Weizman, the first general to join Herut and a nephew of Israel's first President, was a considerable public relations achievement.

The Government participation did not last long, since Gahal left in early 1970 over the acceptance of the Rogers Plan, which included approval of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, a move that was largely dictated by Begin.

Merging into Likud

In the 1977 elections, Herut – now as a part of the Likud – finally reached power, and Menachem Begin became Prime Minister.

In September 1973, Gahal merged with the Free Centre, the National List and the non-parliamentary Movement for Greater Israel to create Likud, again with all parties retaining their independence within the union.

Within Likud, Herut continued to be the dominant party.

In the 1973 elections, Likud capitalized on the government's neglect in the Yom Kippur War, and gained seven seats, totalling 39.

In the following years, Likud sharply criticized the government's accords with Egypt and Syria.

Stormy demonstrations were organized in conjunction with Gush Emunim, signifying an important political alliance.

In the 1977 elections, Likud emerged victorious, with 43 seats, the first time the right had won an election.

Begin became Prime Minister, retaining his post in the 1981 elections.

In 1983, he stood down, and Yitzhak Shamir took over as Herut (and, therefore, Likud) party leader and Prime Minister.

Herut was finally disbanded in 1988, when Likud dissolved its internal factions to become a unitary party.

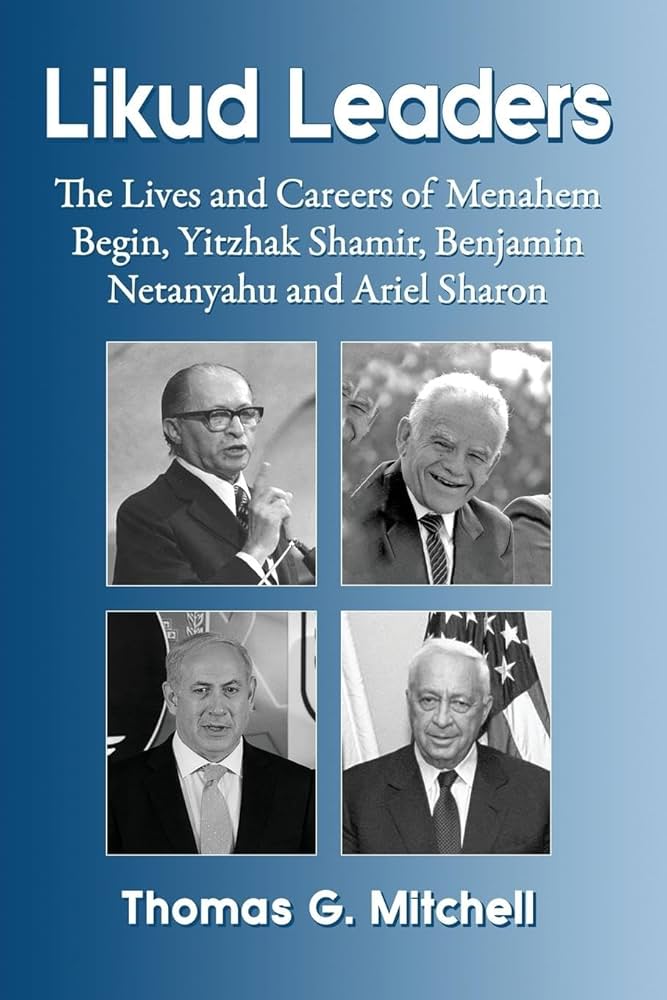

Likud, officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement (Hebrew: הַלִּיכּוּד – תנועה לאומית ליברלית, romanized: HaLikud – Tnu'ah Leumit Liberalit), is a major right-wing political party in Israel.

It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon in an alliance with several right-wing parties.

Likud's landslide victory in the 1977 elections was a major turning point in the country's political history, marking the first time the left had lost power.

In addition, it was the first time in Israel that a right-wing party received the most votes.

After ruling the country for most of the 1980s, the party lost the Knesset election in 1992.

Likud's candidate Benjamin Netanyahu won the vote for prime minister in 1996 and was given the task of forming a government after the 1996 elections following Yitzak Rabin's assassination.

Netanyahu's government fell apart after a vote of no confidence, which led to elections being called in 1999 and Likud losing power to the One Israel coalition led by Ehud Barak.

In 2001 Likud's Ariel Sharon, who replaced Netanyahu following the 1999 election, defeated Barak in an election called by the prime minister following his resignation.

After the party recorded a convincing win in the 2003 elections, Likud saw a major split in 2005 when Sharon left to form the Kadima party.

This resulted in Likud slumping to fourth place in the 2006 elections and losing 28 seats in the Knesset.

Following the 2009 elections, Likud was able to gain 15 seats, and, with Netanyahu back in control of the party, formed a coalition with fellow right-wing parties Yisrael Beiteinu and Shas to take control of the government from Kadima, which earned a plurality, but not a majority.

Netanyahu served as prime minister from then until 2021. Likud had been the leading vote-getter in each subsequent election until April 2019, when Likud tied with Blue and White[30] and September 2019, when Blue and White won one more seat than the Likud.

Likud won the most seats at the 2020 and 2021 elections, but Netanyahu was removed from power in June 2021 by an unprecedented coalition led by Yair Lapid and Naftali Bennett.

He subsequently returned to the office of prime minister after winning the 2022 election.

A member of the party is called a Likudnik (Hebrew: לִכּוּדְנִיק) and the party's election symbol is מחל (Arabic: محل), reflecting the party's origins as an electoral list of several pre-existing parties.

History

Formation and leadership of Begin

The Likud was formed on 13 September 1973 as a secular party by an alliance of several right-wing parties prior to that year's legislative election—Herut, the Liberal Party, the Free Centre, the National List, and the Movement for Greater Israel.

Herut had been the nation's largest right-wing party since growing out of the Irgun in 1948.

It had already been in coalition with the Liberals since 1965 as Gahal, with Herut as the senior partner.

Herut remained the senior partner in the new grouping, which was given the name Likud, meaning "Consolidation", as it represented the consolidation of the Israeli right.

It worked as a coalition under Herut's leadership until 1988, when the member parties merged into a single party under the Likud name.

From its establishment in 1973, Likud enjoyed great support from blue-collar Sephardim.

In its first election Likud won 39 seats, reducing the Alignment's lead to 12.

The party went on to win the 1977 election with 43 seats, finishing 11 seats ahead of the Alignment.

Menachem Begin formed a government with the support of the religious parties, consigning the left wing to opposition for the first time since independence.

A former leader of the hard-line paramilitary Irgun, Begin signed the 1978 Camp David Accords and the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty.

In the 1981 election, the Likud won 48 seats, but formed a narrower government than in 1977.

Likud has long been a loose alliance between politicians committed to different and sometimes opposing policy preferences and ideologies.

The 1981 election highlighted divisions that existed between the populist wing of Likud, headed by David Levy of Herut, and the Liberal wing, who represented a policy agenda of the secular bourgeoisie.

Shamir and Netanyahu's first term

Likud founder Menachem Begin

On 28 August 1983 Begin announced his intention to resign as prime minister.

He was replaced by Yitzhak Shamir, a former commander of the Lehi underground, who defeated Deputy Prime Minister David Levy in a leadership election held by Herut's central committee.

Shamir was seen as a hard-liner, who opposed the Camp David accords and Israel's withdrawal from Southern Lebanon.

The party won 41 seats in the 1984 election, less than the Alignment's 44.

The Alignment was unable to form a government on its own, leading to the formation of a rotation government, led jointly by the Alignment and Likud.

Shimon Peres became the prime minister, with Shamir becoming the foreign minister.

In October 1986, the two switched posts.

The Likud won the 1988 election, defeating the Alignment by a one-seat Margin.

The two parties formed another government, in which Shamir served as prime minister without a rotation.

In 1990 Peres withdrew from the government and led a successful vote of no confidence against it, in what became known as the dirty trick.

Shamir formed a new government with right-wing parties, which served until the 1992 election, in which the Likud was defeated by Yitzhak Rabin's Labor Party.

Shamir stepped down as Likud leader after losing the election in March 1993.

To replace him, the party held its first primary election, in which former United Nations Ambassador Benjamin Netanyahu defeated David Levy, Benny Begin and Moshe Katsav, becoming the Leader of the Opposition.

In 1995, following the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, Shimon Peres, his temporary successor, decided to call early elections in order to give the government a mandate to advance the peace process.

The election was held in May 1996, and included a direct vote for the prime minister in which Netanyahu narrowly defeated Peres, becoming the new prime minister.

Logo of the Likud-Tzomet List from the 1996 election

In 1998 Netanyahu agreed to cede territory in the Wye River Memorandum, which led some Likud MKs, led by Benny Begin (Menachem Begin's son), Michael Kleiner and David Re'em, to break away and form a new party, named Herut – The National Movement. The new party was endorsed by Yitzhak Shamir, who expressed disappointment in Netanyahu's leadership.

Following the withdrawal of his remaining partners, Netanyahu's coalition collapsed in December 1998, resulting in the 1999 election, where Labor's Ehud Barak defeated Netanyahu on a platform promoting the settlement of final status issues.

Following his defeat, Netanyahu stepped down as leader of Likud.

That September, former Defense Minister Ariel Sharon won a leadership election to replace Netanyahu, defeating Jerusalem Mayor Ehud Olmert and former Finance Minister Meir Sheetrit.

Barak's government collapsed in December 2000, several months after the Camp David Summit ended without an agreement, and early elections for Prime Minister were called for February 2001, in which Sharon decisively defeated Barak.

In 2002 Netanyahu challenged Sharon in a leadership election, but was defeated.

During Sharon's tenure, Likud faced an internal split due to Sharon's policy of unilateral disengagement from Gaza and parts of the West Bank, which proved extremely divisive within the party.

Sharon and Kadima split

Sharon's Disengagement Plan alienated him from some Likud supporters and fragmented the party.

He faced several serious challenges to his authority shortly before his departure. The first was in March 2005, when he and Netanyahu, then his finance minister, proposed a budget plan that met fierce opposition from the opposition and parties to the Likud's right.

The plan passed the Knesset's finance committee by a one-vote margin, before being approved by the Knesset by a wider margin later that month.

The second was in September 2005, when Sharon's critics in the Likud, led by Netanyahu, forced a vote in the Likud's central committee on a proposal for an early leadership election, which was defeated by 52% to 48%.

In November, Sharon's opponents within the Likud joined with the opposition to prevent the appointment of three of his associates to the Cabinet, successfully preventing the appointment of two.

On 20 November 2005 Labor announced its withdrawal from Sharon's governing coalition following the election of the left-wing Amir Peretz as its leader.

On 21 November 2005, Sharon announced he would be leaving the Likud and forming a new centrist party, Kadima.

The new party included both Likud and Labor supporters of unilateral disengagement. Sharon also announced that an election would take place in early 2006.

Seven candidates had declared themselves as contenders to replace Sharon as leader: Netanyahu, Uzi Landau, Shaul Mofaz, Yisrael Katz, Silvan Shalom and Moshe Feiglin.

Landau and Mofaz later withdrew, the former in favour of Netanyahu and the latter to join Kadima.

Netanyahu's second term

Netanyahu went on to win a leadership election to replace Sharon in December, obtaining 44.4% of the vote.

Shalom came in a second with 33%, while far-right candidate Moshe Feiglin achieved 12.4% of the vote.

Due to Shalom's performance, Netanyahu guaranteed him the second place on the party's list of Knesset candidates.

Polls before the 2006 election showed a substantial reduction in the Likud's support, with Kadima achieving a dominant polling lead.

A truck canvassing for Likud in Jerusalem in advance of the 2006 election

In January 2006 Sharon suffered a stroke that left him in a vegetative state, leading to his replacement as Kadima leader by Ehud Olmert, who led Kadima to victory in the election, winning 29 seats.

The Likud experienced a substantial loss in support, coming in fourth place and winning only 12, while other right-wing nationalist parties such as Yisrael Beiteinu, which came within 116 votes of overtaking Likud, gained votes.

After the election, Netanyahu was re-elected Likud Leader in 2007, defeating Feiglin and World Likud Chairman Danny Danon.

Following the opening of several criminal investigations against Olmert, he resigned as prime minister on 21 September 2008 and retired from politics.

In the ensuing snap election, held in 2009, Likud won 27 seats, the second-largest number of seats and one seat less than Kadima, now led by Tzipi Livni.

However, Likud's allies won enough seats to allow Netanyahu to form a government, which included Likud, Yisrael Beiteinu, Shas, United Torah Judaism, The Jewish Home, and Labor.

Labor left the coalition in 2011 after party leader Ehud Barak left to form his own party, Independence, that remained a member of Netanyahu's government.

The next year, Netanyahu was re-elected as Likud leader, defeating Moshe Feiglin.

Kadima then joined the coalition in May 2012 before leaving in July.

Following Kadima's withdrawal from the government and amid disagreements related to the 2013 budget, the Knesset was dissolved in October 2012 and a snap election was called for January 2013.

Partnership with Yisrael Beitenu and 2015 election

Several days after the election was called on 25 October 2012, Netanyahu and Yisrael Beitenu leader Avigdor Lieberman announced that their respective political parties would run together on a single ballot in the election under the name Likud Yisrael Beiteinu.

The move led to speculation that Lieberman would eventually seek the leadership of Likud after he stated that he "wanted to become the Prime Minister."

Several days before the election, Lieberman said the parties would not merge, and that their direct partnership would end after the election.

The partnership ultimately lasted until July 2014, when it officially dissolved.

In the 2013 elections the Likud–Yisrael Beiteinu alliance won 31 seats, 20 of which were Likud members.

The second largest party, Yair Lapid's Yesh Atid, won 19.

Netanyahu continued as prime minister after forming a coalition with Yesh Atid, the Jewish Home, and Hatnuah.

The government collapsed in December 2014 due to disagreements over the budget and the proposed Nation-state bill, triggering a snap election the next year.

Likud won the 2015 election, defeating the Zionist Union, an alliance of Labor and Hatnuah, winning 30 seats to the Zionist Union's 24.

The party subsequently formed a government with United Torah Judaism, Shas, Kulanu, and the Jewish Home.

In May 2016, Yisrael Beitenu joined the government, before leaving in December 2018, causing Netanyahu to call a snap election for April 2019.

2019–2022 elections

During the course of the April 2019 Israeli legislative election campaign, Likud facilitated the formation of the Union of Right-Wing Parties between the Jewish Home, Tkuma and Otzma Yehudit by providing a slot on its own electoral list to Jewish Home candidate Eli Ben-Dahan.[124] In the aftermath of the election, Kulanu merged into Likud.[125]

During the September 2019 Israeli legislative election campaign, Likud agreed to a deal with Zehut, whereby the latter party would drop out of the election and endorse Likud in exchange for a ministerial post for its leader, Moshe Feiglin, as well as policy concessions.[126]

Prior to the 2020 Israeli legislative election Gideon Sa'ar unsuccessfully challenged Netanyahu for the Likud leadership.[127] In December of that year, Sa'ar left Likud, along with four other Likud MKs, to form New Hope.[128]

Prior to the 2021 Israeli legislative election, Gesher merged into Likud, receiving a slot on its electoral list.[129] 2021 marked the first time that Likud put a Muslim on its slate, choosing Muslim school principal Nail Zoabi for 39th on its slate.[130]

Likud also facilitated the formation of a joint list between the Religious Zionist Party, Otzma Yehudit and Noam by providing the Religious Zionist Party a slot on the Likud list.[131] On 14 June, after the swearing-in of the 36th government, Ofir Sofer who held the slot, split from the Likud faction and returned to the Religious Zionist Party, decreasing the Likud faction by one to 29 seats in the Knesset.[132][133]

Likud won the most seats in the 2022 Israeli legislative election.

Ideological positions

This article is part of a series on Conservatism in Israel

Ideologies

Parties - Active

Likud

Defunct

Likud emphasizes national security policy based on a strong military force when threatened with continued enmity against Israel. It has shown reluctance to negotiate with its neighbors whom it believes continue to seek the destruction of the Jewish state, that based on the principle of the party founder Menachem Begin concerning the preventive policy to any potential attacks on State of Israel. Its suspicion of neighboring Arab nations' intentions, however, has not prevented the party from reaching agreements with Israel's neighbors, such as the 1979 peace treaty with Egypt. Likud's willingness to enter mutually accepted agreements with neighboring countries over the years is related to the formation of other right-wing parties. Like other right-wing parties in Israel, Likud politicians have sometimes criticized particular Supreme Court decisions, but it remains committed to rule of law principles that it hopes to entrench in a written constitution.[27]

As of 2014, the party remains divided between moderates and hard-liners.[135]

Likud is considered to be the leading party in the national camp in Israeli politics.[136]

Territory

The original 1977 party platform stated that "between the Sea and the Jordan there will only be Israeli sovereignty."[137][138]

The 1999 Likud Party platform emphasized the right of settlement:

The Jewish communities in Judea, Samaria, and Gaza are the realization of Zionist values. Settlement of the land is a clear expression of the unassailable right of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel and constitutes an important asset in the defense of the vital interests of the State of Israel. The Likud will continue to strengthen and develop these communities and will prevent their uprooting.[139]

Similarly, they claim the Jordan River as the permanent eastern border to Israel and it also claims Jerusalem as belonging to Israel.

The 'Peace & Security' chapter of the 1999 Likud Party platform rejects a Palestinian state:

The Government of Israel flatly rejects the establishment of a Palestinian Arab state west of the Jordan river. The Palestinians can run their lives freely in the framework of self-rule, but not as an independent and sovereign state. Thus, for example, in matters of foreign affairs, security, immigration, and ecology, their activity shall be limited in accordance with imperatives of Israel's existence, security and national needs.[139]

With Likud back in power, starting in 2009, Israeli foreign policy is still under review. Likud leader Benjamin Netanyahu, in his "National Security" platform, neither endorsed nor ruled out the idea of a Palestinian state.[140] According to Time, "Netanyahu has hinted that he does not oppose the creation of a Palestinian state, but aides say he must move cautiously because his religious-nationalist coalition partners refuse to give away land."[141]

On 14 June 2009, Netanyahu delivered a speech[142] at Bar-Ilan University (also known as "Bar-Ilan Speech"), at Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, that was broadcast live in Israel and across parts of the Arab world, on the topic of the Middle East peace process. He endorsed for the first time the creation of a Palestinian state alongside Israel, with several conditions.

However, on 16 March 2015, Netanyahu stated in the affirmative, that if he were elected, a Palestinian state would not be created.[143] Netanyahu argued, "anyone who goes to create today a Palestinian state and turns over land, is turning over land that will be used as a launching ground for attacks by Islamist extremists against the State of Israel."[143] Some take these statements to mean that Netanyahu and Likud oppose a Palestinian state. After having been criticised by U.S. White House Spokesperson Josh Earnest for the "divisive rhetoric" of his election campaign, on 19 March 2015, Netanyahu retreated to "I don't want a one-state solution. I want a peaceful, sustainable two-state solution. I have not changed my policy."[144]

The Likud Constitution[145] of May 2014 is more vague and ambiguous. Though it contains commitments to the strengthening of Jewish settlement in the West Bank, it does not explicitly rule out the establishment of a Palestinian state.[citation needed]

Economy

The Likud party claims to support a free market capitalist and liberal agenda, though, in practice, it has mostly adopted mixed economic policies. Under the guidance of finance minister and current party leader Benjamin Netanyahu, Likud pushed through legislation reducing value added tax (VAT), income and corporate taxes significantly, as well as customs duty. Likewise, it has instituted free trade (especially with the European Union and the United States) and dismantled certain monopolies (Bezeq and the seaports). Additionally, it has privatized numerous government-owned companies (e.g. El Al and Bank Leumi), and has moved to privatize land in Israel, which until now has been held symbolically by the state in the name of the Jewish people. Netanyahu was the most ardent free-market Israeli finance minister to date. He argued that Israel's largest labor union, the Histadrut, has so much power as to be capable of paralyzing the Israeli economy, and claimed that the main causes of unemployment are laziness and excessive benefits to the unemployed.[citation needed] Under Netanyahu, Likud has and is likely to maintain a comparatively fiscally conservative economic stance. However, the party's economic policies vary widely among members, with some Likud MKs supporting more leftist economic positions that are more in line with popular preferences.[146]

Palestinians

Likud has historically espoused opposition to Palestinian statehood and support of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. However, it has also been the party that carried out the first peace agreements with Arab states. For instance, in 1979, Likud prime minister Menachem Begin signed the Camp David Accords with Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat, which returned the Sinai Peninsula (occupied by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967) to Egypt in return for peace between the two countries. Yitzhak Shamir was the first Israeli prime minister to meet Palestinian leaders at the Madrid Conference following the Persian Gulf War in 1991. However, Shamir refused to concede the idea of a Palestinian state, and as a result was blamed by some (including United States Secretary of State James Baker) for the failure of the summit.[147] On 14 June 2009, as Prime Minister Netanyahu gave a speech at Bar-Ilan University in which he endorsed a "Demilitarized Palestinian State", though said that Jerusalem must remain the unified capital of Israel.[148]

In 2002, during the Second Intifada, Israel's Likud-led government reoccupied Palestinian towns and refugee camps in the West Bank. In 2005 Ariel Sharon defied the recent tendencies of Likud and abandoned the policy of seeking to settle in the West Bank and Gaza. Though re-elected Prime Minister on a platform of no unilateral withdrawals, Sharon carried out the Gaza disengagement plan, withdrawing from the Gaza Strip, as well as four settlements in the northern West Bank. Though losing a referendum among Likud registered voters, Sharon achieved government approval of this policy by firing most of the cabinet members who opposed the plan before the vote.

Sharon and the faction who supported his disengagement proposals left the Likud party after the disengagement and created the new Kadima party.

This new party supported unilateral disengagement from most of the West Bank and the fixing of borders by the Israeli West Bank barrier.

The basic premise of the policy was that the Israelis have no viable negotiating partner on the Palestinian side, and since they cannot remain in indefinite occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, Israel should unilaterally withdraw.

Netanyahu, who was elected as the new leader of Likud after Kadima's creation, and Silvan Shalom, the runner-up, both supported the disengagement plan; however, Netanyahu resigned his ministerial post before the plan was executed.

As of 2018, most Likud members supported the Jewish settlements in the West Bank and opposed Palestinian statehood and the disengagement from Gaza.

"Anyone who wants to thwart the establishment of a Palestinian state has to support bolstering Hamas and transferring money to Hamas. This is part of our strategy – to isolate the Palestinians in Gaza from the Palestinians in the West Bank" - Benjamin Netanyahu, 2019

Although settlement activity has continued under recent Likud governments, much of the activity outside the major settlement blocs has been to accommodate the Jewish Home, a coalition partner; support within Likud to build outside the blocs is not particularly strong.

Likud, under Netanyahu, is alleged to have intentionally propped up the rule of Hamas in Gaza as a means of dividing the Palestinians politically and using Palestinian extremism drawing the peace process away from a two-state solution.

In the 2019 elections Likud was widely criticized as a "racist party" after scaremongering anti-Arab rhetoric by its members as well as Netanyahu who claimed minority Arabs and Palestinians in Israel as "threats" and "enemies."

Culture

Likud generally advocates free enterprise and nationalism, but it has sometimes compromised these ideals in practice, especially as its constituency has changed.

Its support for populist economic programs are at odds with its free enterprise tradition, but are meant to serve its largely nationalistic, lower-income voters in small towns and urban neighborhoods.

On religion and state, Likud has a moderate stance, and supports the preservation of status quo.

With time, the party has played into the traditional sympathies of its voter base, though the origins and ideology of Likud are secular.

Religious parties have come to view it as a more comfortable coalition partner than Labor.

Likud promotes a revival of Jewish culture, in keeping with the principles of Revisionist Zionism.

Likud emphasizes such Israeli nationalist themes as the use of the Israeli flag and the victory in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

In July 2018, Likud lawmakers voted a controversial Nation-State bill into law which declares Israel as the "nation-state of the Jewish people."

Likud publicly endorses press freedom and promotion of private sector media, which has grown markedly under governments Likud has led.

A Likud government headed by Ariel Sharon, however, closed the popular right-wing pirate radio station Arutz Sheva ("Channel 7"). Arutz Sheva was popular with the Jewish settler movement and often criticised the government from a right-wing perspective.

Historically, the Likud and its pre-1948 predecessor, the Revisionist movement advocated secular nationalism.

However, the Likud's first prime minister and long-time leader Menachem Begin, though secular himself, cultivated a warm attitude to Jewish tradition and appreciation for traditionally religious Jews—especially from North Africa and the Middle East.

This segment of the Israeli population first brought the Likud to power in 1977.

Many Orthodox Israelis find the Likud a more congenial party than any other mainstream party, and in recent years also a large group of Haredim, mostly modern Haredim, joined the party and established the Haredi faction in the Likud.

Foreign policy

Since the 1990s, Likud has advocated a hardline stance against Iran and its proxy militias such as the Lebanese Hezbollah.

Likud prime ministers Ariel Sharon and Benjamin Netanyahu have typically pursued improved relations with Russia, with Likud using posters of Netanyahu meeting Russian president Vladimir Putin during its September 2019 Israeli legislative election campaign.

However, since the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Likud has been divided, with party leader Netanyahu seeking to maintain working relations with Russia and avoid involvement in the conflict, while some MKs, such as Nir Barkat and Yuli Edelstein, have advocated closer alignment with the West against Russia and support for Ukraine in the Russo-Ukrainian war.

The Likud government during the 2010s advocated closer ties with Japan, China and India, in order to reduce Israel's dependency on Western Europe.

In 2017 Netanyahu described closer Israeli alignment with China as a "marriage made in heaven."

Likud has also maintained connections with the ruling political party in India, the Bharatiya Janata Party.

Likud governments have pursued close ties with the Republican Party in the United States, leading to a perception of preference for the Republicans over the rival Democratic Party.

In 2015 Netanyahu delivered an address to the Republican-held United States Congress without consulting the Democratic presidential administration at the time.

The NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 drew criticism from the Likud foreign minister Ariel Sharon, who described it as "brutal interventionism."

Relations between Serbia and Israel improved during the Netanyahu-led Likud government of the 2010s.

Likud has had long-term political ties to the Hungarian ruling party Fidesz, which has led to warm diplomatic relations between Netanyahu's Likud governments and the Hungarian governments of Viktor Orbán.

In recent years, Likud has cultivated ties with European right-wing populist political parties, including the Spanish Vox, the Italian Lega, the Portuguese Chega, the Dutch Party for Freedom, the French National Rally, the Sweden Democrats,the Danish People's Party, the Alliance for the Union of Romanians and the Belgian Vlaams Belang.

Composition (1973–1988)

Name Ideology Position Leader Herut (1973–1988)

Menachem Begin (1949–1983)

Yitzhak Shamir (1983–1988)

Liberal (1973–88)

Elimelekh Rimalt (1972–1975)

Simcha Erlich (1976–1983)

Pinchas Goldstein (1983–1988)

National List

(1973–1976; 1981)

Yigal Hurvitz (1970–1976)

Yitzhak Peretz (1981)

Free Centre

(1973–1977)

Right-wingShmuel Tamir (1967–1977) Independent Centre

(1975–76)

Right-wingEliezer Shostak (1975–76) Movement for Greater Israel

(1973–1976)

Right-wingAvraham Yoffe (1967–1976) La'am

(1976–1984)

Yigal Hurvitz (1976–1984)

Eliezer Shostak (1976–1984)

Leaders

Menachem Begin - 1973, 1983, 1977–1983, 1977, 1981

Yitzhak Shamir - 1983, 1993, 1983–1984, 1986–1992, 1984, 1988, 1992, 1983, 1984, and 1992

Benjamin Netanyahu - 1993, 1999, 1996–1999, 1996, 1999, 1993, and 1999 (Jan)

Ariel Sharon - 1999 2005 2001–2006 2001, 2003 1999 (Sep) and 2002

Benjamin Netanyahu - 2005, 2009–2021, 2022–2006, 2009, 2013, 2015, Apr 2019, Sep 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2005, 2007, 2012, 2014, and 2019.

Leader election process

During Begin's tenure as leader of Herut/Likud, his leadership was effectively unchallenged.

From 1983 through 1992, Herut/Likud elected its party leaders through votes held in party agencies.

The 1983 and 1984 Herut leadership elections were undertaken through a vote of Herut's Central Committee.

The day after Yitzhak Shamir won the 1983 secret ballot vote of the Herut Central Committee to obtain Herut's party leadership, the party leaders of the other Likud coalition member parties announced that they agreed to have Shamir lead the Likud coalition.

The 1992 Likud leadership election was the first held after Likud became a unified party. The 1992 leadership election was held as a vote of the Likud Central Committee.

After 1992, the party moved to electing its leaders through votes of its general membership, with the first such vote taking place in 1993.

Party list selection process

Prior to the 2006 election, the Likud's Central Committee relinquished control of selecting the Knesset list to the "rank and file" members at Netanyahu's behest.

The aim was to improve the party's reputation, as the central committee had gained a reputation for corruption.

Current MKs

Likud currently has 32 Knesset members. They are listed below in the order that they appeared on the party's list for the 2022 elections.

Eli Cohen (replaced by Osher Shekalim on 15 February 2023)

Yoav Galant (replaced by Afif Abed on 5 January 2024)

Dudi Amsalem (replaced by Avihai Boaron on 31 March 2023, who was replaced by Galit Distel-Atbaryan on 14 October 2023)

Yoav Kisch (replaced by Sasson Guetta on 26 March 2023)

Miri Regev (replaced by Keti Shitrit on 15 February 2023)

Miki Zohar (replaced by Dan Illouz on 6 January 2023)

Amichai Chikli (replaced by Amit Halevi on 17 January 2023)

Danny Danon (replaced by Avihai Boaron on 1 July 2024)

Idit Silman (replaced by Eti Atiya on 7 January 2023)

Galit Distel-Atbaryan (replaced by Moshe Passal on 12 March 2023)

Haim Katz (replaced by Ariel Kallner on 6 January 2023)

Ofir Akunis (replaced by Tsega Melaku on 9 February 2023)

Party organs

Likud Executive

Director General of the Likud: Zuri Siso

Deputy DG, head of the Municipal Division, head of the Computer Division: Zuri Siso

Manager of the Likud Chairman's Office: Hanni Blaivais

Director of Foreign Affairs and Likud spokesperson: Eli Hazan

Likud Central Committee

The Central Committee decides on all matters between party conferences, with the exceptions of matters designated to another organ. As of 2022, the chairman of the Central Committee is Haim Katz.

The Central Committee has a considerable number of members. For example, in one vote, 3,050 members took part in 2005.

Likud Secretariat

The secretariat is the body that elects the director general of the part and the heads various departments. It defines their powers and supervises their activities. As of 2022 the chairman of the secretariat is Haim Katz.

Likud Court

The Court is the supreme judicial organ in all matters of the party.

Legal Advisor

The Legal Advisor advises the party and its bodies in the matters of the state law and the Party constitution and represents the party before external authorities.

The Legal Advisor has a significant power and may overturn the decisions of most of the party bodies, including the Central Committee.

As of 2022 the Legal Advisor of the Likud Movement is Avi Halevy.

Likud Youth Movement

The Likud Youth Movement (Noar HaLikud [he], lit. 'Likud Youth', sometimes called 'Young Likud'), is the official body in charge of all young members of Likud.

It is a member group of the International Young Democrat Union.

Monument in memory of the eight members of Irgun and the two members of Lehi, hung by British authorities between 1938 and 1947.

Political news, commentary for the enraged reader

contact@dailybeastie.com

© 2025 DailyBeastie.Com - All rights reserved.